Spatial Structures in Ecological Models

What this document will cover:

Spatial structures

├── Why go spatial?

│ └── autocorrelation

├── How to go spatial?

│ └── Background, examples, and considerations by data type

│ ├── Point referenced data

│ ├── Areal data

│ ├── Point-pattern data

│ └── Movement data

├── What about mixed data types?

│ ├── Change of support

│ ├── Joint likelihoods

│ └── Spatial misalignment

├── What about model selection?

│ └── Spatial validation methods

├── What to watch out for?

│ ├── Common pitfalls

│ ├── Computational limitation

│ └── Software considerations

└── Resources

Why include spatial structures in your model?

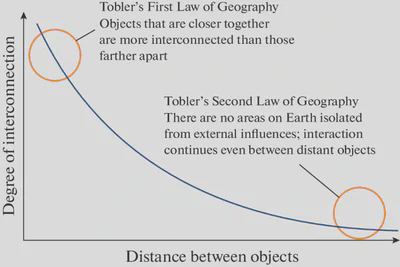

Tobler’s First law Geography (a.k.a. spatial autocorrelation):

[…] everything is related to everything else, but near things are more related than distant things."

- Waldo Tobler 1970 (link to paper)

Put more explicitely: measurements of ecological phenomena are more interconnected at close distances versus distant ones

Further: Ignoring spatial autocorrelation leads to…

- Biased parameter estimates

- Inflated significance (increased chance of Type-I error)

- Reduced model precision

- Inaccurate model selection

- Violated statistical assumptions (iid errors)

- Poor predictive accuracy

- Non-demonic intrusion 😈

How to account for spatial autocorrelation in my model?

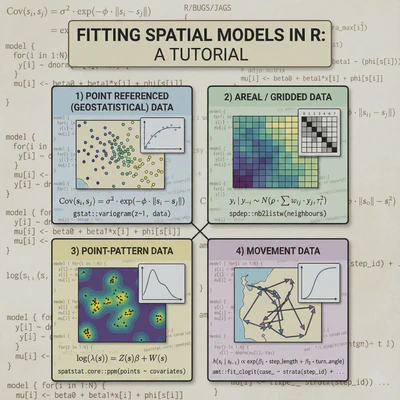

First, what type of spatial data do you have?

Each data type has specialized methods, assumptions, and computational considerations.

Data types:

- Point-Referenced Data (geostatistical data)

- Areal/Lattice Data (regional/grid data)

- Point Pattern Data (locations are the response)

- Movement/Trajectory Data (tracks and telemetry)

Note: Many ecological studies combine multiple data types! We’ll breifly discuss integration approaches.

1. Point-Referenced Data

Measurements at specific geographic coordinates

What is Point-Referenced Data?

Definition: Observations collected at specific locations, representing a continuous spatial process.

Ecological Examples:

- Species abundance at survey points

- Vegetation cover at plot locations

- Soil samples across a landscape

- Individual tree measurements in a forest

Key characteristic: Locations are fixed by design, not random.

A visual example

Typical scenario:

- 50-5000 sampling locations

- Environmental covariates at each point

- Response variable (abundance, presence, etc.)

- Want to predict across unsampled locations

Common Questions

- How does my response vary across space?

- What drives spatial patterns?

- Can I predict to new locations?

- Is there residual spatial autocorrelation?

Point-Referenced data: The Core Challenge

After accounting for environmental covariates, you often have residual spatial structure:

$$y(\mathbf{s}) = \mathbf{X}(\mathbf{s})\boldsymbol{\beta} + w(\mathbf{s}) + \epsilon(\mathbf{s})$$

Where:

- $y(\mathbf{s})$ = response at location $\mathbf{s}$

- $\mathbf{X}(\mathbf{s})\boldsymbol{\beta}$ = fixed effects (environmental covariates)

- $w(\mathbf{s})$ = spatial random effect (what we need to model!)

- $\epsilon(\mathbf{s})$ = non-spatial noise

Point-Referenced data: Five Approaches

We’ll cover five main approaches, organized by their relationship to Gaussian Processes:

- Full Gaussian Processes (GPs) - theoretical gold standard

- SPDE Approximation - Exact GPs using basis functions

- Low-Rank Gaussian Processes - Approximate GPs for efficiency

- Nearest Neighbor GPs - Local GP approximations

- Spatial Splines - Alternative smoothing framework (non-GP)

Each represents different trade-offs between accuracy, computation, and flexibility.

Understanding the GP Family Tree

Conceptual Relationships

Full GP ($O(n^3)$)

- Exact, but computationally prohibitive for large $n$

Reduced-Rank GP Approximations:

- SPDE - Exact Matérn GP via finite elements (sparse matrices)

- Low-Rank GP - Approximate using subset of basis functions

- Nearest Neighbor GP - Local conditioning on nearby points

Alternative Framework:

- Splines - Smoothness penalty instead of covariance structure

Key insight: Methods 2-4 are all ways to make GPs computationally feasible while maintaining the probabilistic framework.

Method 1: Full Gaussian Processes

The gold standard for point-referenced data

$$w(\mathbf{s}) \sim \mathcal{GP}(0, k(\mathbf{s}, \mathbf{s}’))$$

Covariance function defines spatial correlation:

$$k(\mathbf{s}, \mathbf{s}’) = \sigma^2 \exp\left(-\frac{||\mathbf{s} - \mathbf{s}’||^2}{2\ell^2}\right)$$

Parameters:

- $\sigma^2$ = spatial variance (how much spatial variation?)

- $\ell$ = length-scale (how far does correlation extend?)

Full GP: Covariance Functions

Matérn family (most common in ecology):

$$k(d) = \sigma^2 \frac{2^{1-\nu}}{\Gamma(\nu)}\left(\sqrt{2\nu}\frac{d}{\ell}\right)^\nu K_\nu\left(\sqrt{2\nu}\frac{d}{\ell}\right)$$

Special cases:

- $\nu = 0.5$ → Exponential (rough surfaces)

- $\nu = 1.5$ → Once differentiable (good default)

- $\nu = 2.5$ → Twice differentiable

- $\nu \to \infty$ → Squared exponential (infinitely smooth)

Practical Advice

Start with $\nu = 1.5$ (good default) or estimate it if you have enough data.

Full GP: The Computational Problem

Standard GP inference requires:

- Inverting an $n \times n$ covariance matrix: $O(n^3)$ operations

- Storing the matrix: $O(n^2)$ memory

Practical limits:

- ~1,000 locations: comfortable

- ~5,000 locations: challenging

- 10,000+ locations: infeasible

This is why we need approximations!

Reduced rank GPs make modeling feasible for realistic ecological datasets.

Full GP: R Implementation

library(geoR)

library(fields)

# Using geoR for ML estimation

geo_data <- as.geodata(data, coords.col = 1:2, data.col = 3)

# Fit variogram

vario <- variog(geo_data, max.dist = 100)

plot(vario)

# Fit Matérn model

fit_ml <- likfit(

geo_data,

ini.cov.pars = c(1, 10), # Initial sigma^2, range

cov.model = "matern",

kappa = 1.5, # nu parameter

fix.kappa = TRUE

)

summary(fit_ml)

# Kriging predictions

pred_grid <- expand.grid(

x = seq(min(data$x), max(data$x), length = 50),

y = seq(min(data$y), max(data$y), length = 50)

)

kc <- krige.control(

type.krige = "OK",

obj.model = fit_ml

)

predictions <- krige.conv(

geo_data,

locations = pred_grid,

krige = kc

)

# Plot predictions

image.plot(predictions$predict)

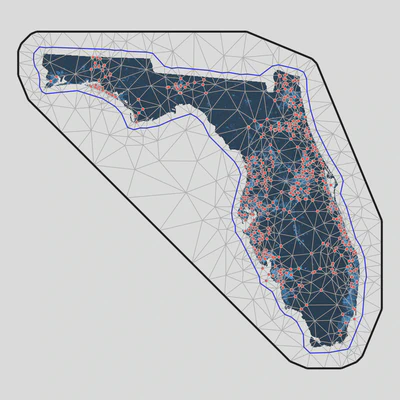

Method 2: SPDE Approximation

The SPDE approach (Lindgren et al. 2011) makes GPs computationally tractable!

Key insight: A Matérn GP is the solution to a stochastic partial differential equation:

$$(\kappa^2 - \Delta)^{\alpha/2}(\tau w(\mathbf{s})) = \mathcal{W}(\mathbf{s})$$

Critical distinction: SPDE provides an exact representation of the Matérn GP, not an approximation.

Practical result:

- Represent continuous GP using finite element basis functions

- Sparse precision matrices enable fast computation

- Reduces $O(n^3)$ to approximately $O(n^{3/2})$ or better

- Makes analysis of 10,000+ locations feasible

SPDE: How It Works

- Create triangular mesh over study area

- GP represented exactly at mesh vertices

- Values between vertices interpolated

Mesh construction is critical:

- Finer mesh = better approximation

- Coarser mesh = faster computation

- Balance accuracy and speed

- Extend mesh beyond study area

Rule of Thumb: Mesh resolution should be finer than the spatial range ($\ell$), ideally <1k

SPDE: R Implementation with sdmTMB

library(sdmTMB)

# Create mesh object that contains matrices to apply the SPDE approach

mesh <- make_mesh(pcod, xy_cols = c("X", "Y"), cutoff = 10)

# Fit a spatial model with a smoother for depth:

fit <- sdmTMB(

density ~ s(depth),

data = pcod,

mesh = mesh,

family = tweedie(link = "log"),

spatial = "on"

)

# Run some basic sanity checks on our model:

sanity(fit)

# Use the ggeffects package to plot the smoother effect:

ggeffects::ggpredict(fit, "depth [50:400, by=2]") %>%

plot()

# Obtain spatial predictions:

p <- predict(fit, newdata = qcs_grid)

# Map predictions

ggplot(p, aes(X, Y, fill = exp(est))) + geom_raster() +

scale_fill_viridis_c(trans = "sqrt")

SPDE: R Implementation with INLA

library(INLA)

library(inlabru)

# Create mesh over study region

mesh <- inla.mesh.2d(

loc = cbind(data$x, data$y), # Data locations

max.edge = c(5, 20), # Inner and outer max edge

cutoff = 1, # Min distance between mesh nodes

offset = c(10, 30) # Inner and outer extension

)

# Visualize mesh

plot(mesh)

points(data$x, data$y, col = "red", pch = 16)

# Define SPDE model (Matérn with alpha=2 gives nu=1)

spde <- inla.spde2.matern(

mesh = mesh,

alpha = 2 # alpha = nu + d/2, where d=2 (spatial dimensions)

)

# Create projection matrix (links data locations to mesh)

A <- inla.spde.make.A(

mesh = mesh,

loc = cbind(data$x, data$y)

)

# Stack data for INLA

stack <- inla.stack(

data = list(y = data$abundance),

A = list(A, 1),

effects = list(

spatial = 1:spde$n.spde,

data.frame(

Intercept = 1,

elevation = data$elevation,

forest_cover = data$forest_cover

)

)

)

# Fit model

formula <- y ~ -1 + Intercept + elevation + forest_cover +

f(spatial, model = spde)

result <- inla(

formula,

family = "poisson",

data = inla.stack.data(stack),

control.predictor = list(

A = inla.stack.A(stack),

compute = TRUE

),

control.compute = list(

dic = TRUE,

waic = TRUE,

cpo = TRUE

)

)

summary(result)

# Extract spatial field estimates

spde_result <- inla.spde2.result(result, "spatial", spde)

SPDE: Making Predictions

# Create prediction grid

pred_coords <- expand.grid(

x = seq(min(data$x), max(data$x), length = 100),

y = seq(min(data$y), max(data$y), length = 100)

)

# Projection matrix for predictions

A_pred <- inla.spde.make.A(

mesh = mesh,

loc = as.matrix(pred_coords)

)

# Create prediction stack

stack_pred <- inla.stack(

data = list(y = NA), # NA for prediction

A = list(A_pred, 1),

effects = list(

spatial = 1:spde$n.spde,

data.frame(

Intercept = 1,

elevation = mean(data$elevation),

forest_cover = mean(data$forest_cover)

)

)

)

# Combine with original data

stack_full <- inla.stack(stack, stack_pred)

# Refit model with prediction stack

result_pred <- inla(

formula,

family = "poisson",

data = inla.stack.data(stack_full),

control.predictor = list(

A = inla.stack.A(stack_full),

compute = TRUE,

link = 1

)

)

# Extract predictions

idx_pred <- inla.stack.index(stack_full, "stack_pred")$data

pred_coords$mean <- result_pred$summary.fitted.values$mean[idx_pred]

pred_coords$sd <- result_pred$summary.fitted.values$sd[idx_pred]

# Map predictions

library(ggplot2)

ggplot(pred_coords, aes(x, y, fill = mean)) +

geom_raster() +

scale_fill_viridis_c() +

coord_equal() +

theme_minimal()

Method 3: Low-Rank Gaussian Processes

Reduced-rank GP approximations for computational efficiency

Key idea: Approximate the spatial field using a smaller set of basis functions:

$$w(\mathbf{s}) \approx \sum_{j=1}^{m} \beta_j \phi_j(\mathbf{s})$$

Where $m « n$ (number of basis functions much less than data points).

Common approaches:

- Predictive Processes - GPs at knot locations

- Subset of Regressors - GP conditioning on subset

- Fixed Rank Kriging - Low-rank spatial covariance

Low-Rank GP: Predictive Processes

Concept:

- Choose $m$ knot locations (e.g., 50-200 knots)

- Define full GP at knots

- Predict data locations as function of knot GPs

$$w(\mathbf{s}) \approx \mathbf{C}(\mathbf{s}, \mathbf{s}^) \mathbf{C}(\mathbf{s}^, \mathbf{s}^)^{-1} w(\mathbf{s}^)$$

Where $\mathbf{s}^*$ are knot locations.

Computational cost: $O(nm^2 + m^3)$ - dominated by $m^3$ for reasonable $n$

Choosing m More knots = better approximation but slower. Start with $m = \sqrt{n}$ or 50-100 knots.

Low-Rank GP: R Implementation

library(spBayes)

library(MBA) # For knot placement

# Define knots (can be data locations or regular grid)

n_knots <- 100

# Create regular grid of knots

knot_coords <- expand.grid(

x = seq(min(data$x), max(data$x), length = sqrt(n_knots)),

y = seq(min(data$y), max(data$y), length = sqrt(n_knots))

)

# Alternatively, use k-means clustering for adaptive knots

# kmeans_result <- kmeans(cbind(data$x, data$y), centers = n_knots)

# knot_coords <- kmeans_result$centers

# Prepare data for spBayes

coords <- cbind(data$x, data$y)

X <- model.matrix(~ elevation + forest_cover, data = data)

y <- data$abundance

# Set up predictive process model

n_samples <- 5000

starting <- list(

"phi" = 3/max(dist(coords)), # 3/max_distance rule of thumb

"sigma.sq" = 1,

"tau.sq" = 0.1

)

tuning <- list(

"phi" = 0.1,

"sigma.sq" = 0.1,

"tau.sq" = 0.1

)

priors <- list(

"beta.Flat",

"phi.Unif" = c(3/max(dist(coords)), 3/min(dist(coords))),

"sigma.sq.IG" = c(2, 1),

"tau.sq.IG" = c(2, 0.1)

)

# Fit predictive process model

pp_model <- spLM(

y ~ X - 1,

coords = coords,

knots = as.matrix(knot_coords),

starting = starting,

tuning = tuning,

priors = priors,

cov.model = "exponential",

n.samples = n_samples,

verbose = TRUE,

n.report = 500

)

# Burn-in and thin

burn_in <- 0.5 * n_samples

pp_samples <- spRecover(

pp_model,

start = burn_in,

thin = 2

)

summary(pp_samples)

Low-Rank GP: Alternative with FRK

library(FRK) # Fixed Rank Kriging

# Create basis functions (2 resolutions)

basis <- auto_basis(

data = data.frame(x = data$x, y = data$y),

nres = 2, # Number of resolutions

type = "bisquare" # Basis function type

)

# Prepare data

sp_data <- SpatialPointsDataFrame(

coords = cbind(data$x, data$y),

data = data.frame(

z = data$abundance,

elevation = data$elevation,

forest_cover = data$forest_cover

)

)

# Fit FRK model

frk_model <- FRK(

f = z ~ elevation + forest_cover,

data = list(sp_data),

basis = basis,

response = "poisson" # Or "gaussian" for continuous

)

# Predictions

pred_grid <- SpatialPoints(

coords = cbind(pred_coords$x, pred_coords$y)

)

predictions <- predict(frk_model, newdata = pred_grid)

Method 4: Nearest Neighbor Gaussian Processes

For very large datasets (>10,000 points)

Key idea: Each location conditions only on its $m$ nearest neighbors (typically $m = 10-30$)

$$w(\mathbf{s}_i) | {w(\mathbf{s}_j): j \in \mathcal{N}_m(i)} \sim \text{Normal}(\boldsymbol{\mu}_i, \sigma^2_i)$$

Advantages:

- Scales to massive datasets (100,000+ locations)

- Maintains proper GP framework

- Computationally efficient: $O(nm^3)$

- Can be highly accurate

Key development: Datta et al. (2016) - Nearest Neighbor Gaussian Process

Nearest Neighbor GP: How It Works

Response model: Define ordered observations $\mathbf{y} = (y_1, \ldots, y_n)$

Neighbor set: For each $i$, define $\mathcal{N}_m(i)$ = indices of $m$ nearest neighbors (prior to $i$)

Conditional specification:

$$p(w_i | w_1, \ldots, w_{i-1}) = p(w_i | w_{\mathcal{N}_m(i)})$$

Result: Sparse precision matrix, fast computation

The ordering of your data affects results!

Common factors to order by:

- by coordinate

- space-filling curves

- random

Nearest Neighbor GP: R package spNNGP

library(spNNGP)

# Prepare data

coords <- cbind(data$x, data$y)

X <- model.matrix(~ elevation + forest_cover, data = data)

y <- data$abundance

# Set up NNGP model

n_neighbors <- 15 # Typical range: 10-30

# Starting values

starting <- list(

"phi" = 3/max(dist(coords)),

"sigma.sq" = 1,

"tau.sq" = 0.1,

"beta" = rep(0, ncol(X))

)

# Tuning parameters

tuning <- list(

"phi" = 0.5,

"sigma.sq" = 0.1,

"tau.sq" = 0.1,

"beta" = 0.1

)

# Prior distributions

priors <- list(

"beta.Flat",

"phi.Unif" = c(3/max(dist(coords)), 3/0.01),

"sigma.sq.IG" = c(2, 1),

"tau.sq.IG" = c(2, 0.1)

)

# Fit NNGP model

nngp_model <- spNNGP(

formula = y ~ X - 1,

coords = coords,

starting = starting,

method = "response",

n.neighbors = n_neighbors,

tuning = tuning,

priors = priors,

cov.model = "exponential",

n.samples = 5000,

n.omp.threads = 4, # Parallel threads

verbose = TRUE

)

# Posterior summaries

summary(nngp_model$p.beta.samples)

summary(nngp_model$p.theta.samples)

# Predictions at new locations

pred_coords_mat <- as.matrix(pred_coords[, c("x", "y")])

X_pred <- cbind(

1,

mean(data$elevation),

mean(data$forest_cover)

)

predictions <- predict(

nngp_model,

X.0 = X_pred,

coords.0 = pred_coords_mat,

n.omp.threads = 4

)

# Extract mean predictions

pred_mean <- apply(predictions$p.y.0, 1, mean)

pred_sd <- apply(predictions$p.y.0, 1, sd)

Nearest Neighbor GP: R package spAbundance

library(spAbundance)

# Fit Bayesian heirarchical distance sampling model

out <- spDS(

# State process formula

abund.formula = ~ forest + grass ,

# Observation process formula

det.formula = ~ day + I(day^2) + wind,

# Model controls

data = dat.MODO, n.batch = 800, batch.length = 25,

accept.rate = 0.43, cov.model = "exponential",

transect = 'point', det.func = 'halfnormal',

NNGP = TRUE, n.neighbors = 15, n.burn = 10000,

n.thin = 5, n.chains = 3, verbose = FALSE)

# Posterior predictive check

ppcAbund(out, fit.stat = 'freeman-tukey', group = 1) %>%

summary()

# Model selection

waicAbund(out)

# Predictions

out.pred <- predict(out, predictors, coordinates, verbose = FALSE)

Method 5: Spatial Splines

Alternative framework: Not based on Gaussian Processes

Key idea: Approximate spatial surface with smooth basis functions

$$w(\mathbf{s}) = \sum_{k=1}^{K} \beta_k \phi_k(\mathbf{s})$$

Distinguishing features:

- Minimize roughness penalty (not maximize likelihood of covariance)

- Deterministic smoothing approach

- Can have Bayesian interpretation (splines as random effects)

- Very fast computation

- Different uncertainty quantification

Spatial Splines: Types

Thin plate splines - Optimal smoothness properties

Minimize: $$\sum_{i=1}^n (y_i - f(\mathbf{s}_i))^2 + \lambda \int \int \left[\left(\frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x^2}\right)^2 + 2\left(\frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x \partial y}\right)^2 + \left(\frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial y^2}\right)^2\right] dx,dy$$

Tensor product splines - Product of 1D basis functions

Radial basis functions - Distance-based kernels

When to Use Splines

Splines are excellent for quick exploratory analysis and when you dont need explicit covariance modeling.

Spatial Splines: R Implementation with mgcv

library(mgcv)

# Basic spatial smooth

model_basic <- gam(

abundance ~ s(x, y, bs = "tp", k = 50),

family = poisson,

data = data,

method = "REML"

)

# With covariates

model_full <- gam(

abundance ~

s(elevation, k = 10) +

s(forest_cover, k = 10) +

s(x, y, bs = "tp", k = 100),

family = poisson,

data = data,

method = "REML"

)

# Check model

summary(model_full)

gam.check(model_full) # Check basis dimensions and residuals

# Plot effects

plot(model_full, pages = 1, scheme = 2)

# Spatial smooth only

plot(model_full, select = 3, scheme = 2, asp = 1)

# Predictions

pred_data <- expand.grid(

x = seq(min(data$x), max(data$x), length = 100),

y = seq(min(data$y), max(data$y), length = 100),

elevation = mean(data$elevation),

forest_cover = mean(data$forest_cover)

)

pred_data$fit <- predict(model_full, pred_data, type = "response")

pred_data$se <- predict(model_full, pred_data, type = "response", se.fit = TRUE)$se.fit

# Map predictions

library(ggplot2)

ggplot(pred_data, aes(x, y, fill = fit)) +

geom_raster() +

scale_fill_viridis_c() +

coord_equal() +

labs(fill = "Predicted\nAbundance") +

theme_minimal()

Spatial Splines: Tensor Products

# Tensor product of marginal smooths (useful for anisotropy)

model_tensor <- gam(

abundance ~

s(elevation) +

te(x, y, k = c(10, 10)), # Tensor product

family = poisson,

data = data,

method = "REML"

)

# Adaptive smooth (varying complexity)

model_adaptive <- gam(

abundance ~

s(elevation) +

s(x, y, bs = "ad", k = 100), # Adaptive smooth

family = poisson,

data = data,

method = "REML"

)

# Soap film smooth (with boundary)

# Useful when study area has complex shape

library(sf)

boundary <- st_read("study_boundary.shp")

# Convert boundary to appropriate format

# (See mgcv::smooth.construct.so.smooth.spec for details)

Point-Referenced: Comprehensive Comparison

| Method | Framework | Complexity | Speed | n Limit | Uncertainty | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full GP | GP | $O(n^3)$ | Slow | ~1000 | Exact | Small datasets, methodological work |

| SPDE | GP (exact) | $O(n^{3/2})$ | Fast | ~50,000 | Exact | Medium-large datasets, Bayesian inference |

| Low-Rank GP | GP (approx) | $O(nm^2 + m^3)$ | Medium | ~10,000 | Bayesian | Moderate datasets, flexible |

| NN-GP | GP (approx) | $O(nm^3)$ | Fast | 100,000+ | Bayesian | Very large datasets |

| Splines | Non-GP | $O(n)$ | Very Fast | 50,000+ | Frequentist | Quick analysis, exploration |

Key R packages

Full GP: gstat (classical geostats) + fields (spatial random fields)

SPDE:

INLA+inlabru(highly customizable)sdmTMB(user friendly, single species) ortinyVAST(multi-species)

Low-Rank GP: spBayes or nimble (highly customizable Bayesian modeling)

Nearest Neighbor GP:

spNNGP- Nearest Neighbor Gaussian ProcessesspAbundance&spOccupancy(Hierarchical Bayesian models)

Splines: mgcv (GAMs) or mvgams (Hierarchical Bayesian GAMs)

Common Pitfalls and Solutions

Watch Out For:

Over-smoothing:

- Splines: Check

gam.check()and increasekif needed - GPs: Ensure spatial range parameter is estimable

Under-smoothing:

- Creates overly complex surfaces that don’t generalize

- Use cross-validation to check predictive performance

Computational Issues:

- Start with small datasets to test workflow

- Use reduced-rank methods before attempting full GP

- Consider parallelization for MCMC-based methods

Mesh/Knot Placement:

- SPDE: Mesh should extend beyond data

- Low-Rank: Try different knot configurations

Validation and Model Checking

Essential diagnostics for all methods:

# 1. Residual spatial autocorrelation

library(spdep)

coords <- cbind(data$x, data$y)

neighbors <- dnearneigh(coords, 0, max_distance)

weights <- nb2listw(neighbors)

moran.test(residuals(model), weights)

# 2. Variogram of residuals

library(gstat)

resid_variogram <- variogram(

residuals ~ 1,

locations = ~x+y,

data = data

)

plot(resid_variogram) # Should be flat if spatial structure captured

# 3. Spatial cross-validation

library(blockCV)

spatial_blocks <- cv_spatial(

x = data_sf,

column = "response",

k = 5,

size = 10000

)

# 4. Predictive performance

# Compare RMSE, MAE, coverage of prediction intervals

Integration with Covariates

All methods can include environmental covariates:

Additive structure: $$y(\mathbf{s}) = \beta_0 + \sum_{j=1}^p f_j(x_j(\mathbf{s})) + w(\mathbf{s}) + \epsilon(\mathbf{s})$$

Where $f_j$ can be:

- Linear effects: $\beta_j x_j$

- Smooth effects: Spline or polynomial

- Interactions: $x_j \times x_k$ or tensor products

Interpretation Challenge

Spatial random effects can “absorb” covariate effects if covariates are spatially structured. Consider restricted spatial regression or spatial confounding adjustments.

Advanced Topics

Extensions of point-referenced methods:

- Non-stationary GPs - Spatial parameters vary across space

- Anisotropic models - Correlation depends on direction

- Space-time models - Add temporal dimension

- Multivariate spatial models - Multiple responses

- Preferential sampling - Locations not random

- Measurement error - Covariate uncertainty

These typically require specialized implementations of the core methods.

Summary: Point-Referenced Data

Key Takeaways

- Gaussian Processes provide the theoretical foundation

- SPDE offers exact GP representation with computational efficiency

- Low-Rank and NN-GP are approximations that scale to large datasets

- Splines provide a fast alternative framework

- Choice depends on: dataset size, computational resources, and inference goals

- Start simple (splines) and add complexity as needed

- Always validate using spatial cross-validation

- Check residuals for remaining spatial structure

Resources and Further Reading

Key Papers:

- Lindgren et al. (2011) “An explicit link between Gaussian fields and GMRFs” JRSS-B

- Datta et al. (2016) “Hierarchical Nearest-Neighbor Gaussian Process Models” JASA

- Banerjee et al. (2008) “Gaussian predictive process models” JRSS-B

- Wood (2017) Generalized Additive Models: An Introduction with R

Online Resources:

- R-INLA website - Tutorials and examples

- mgcv documentation

- Spatial Data Science with R

Books:

- Banerjee et al. (2014) Hierarchical Modeling and Analysis for Spatial Data

- Cressie & Wikle (2011) Statistics for Spatio-Temporal Data

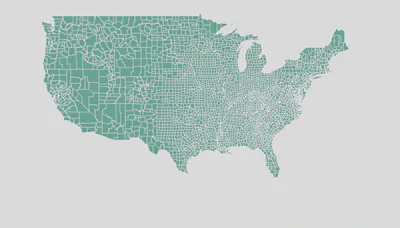

2. Areal / Lattice Data

Aggregated data in discrete spatial units

What is Areal Data?

Definition: Data aggregated to discrete spatial units with defined boundaries.

Ecological Examples:

- Species counts by county or grid cell

- Disease prevalence by administrative unit

- Land cover by hexagonal bins

- Population density by watershed

- Camera trap detections by site

Key characteristic: Space is partitioned into units; data are aggregated within units.

Areal Data: Visual Example

Typical scenario:

- 20-5000 spatial units (polygons or grid cells)

- Clear neighborhood structure

- Count or aggregated data per unit

- Want to account for spatial dependence

Common Questions

- Are neighboring units more similar?

- How do I borrow strength across space?

- Can I smooth noisy estimates?

- Should I worry about edge effects?

Areal Data: Neighborhood Structure

Critical concept: Who are my neighbors?

Common definitions:

- Rook adjacency - shared border

- Queen adjacency - shared border or corner

- Distance-based - within threshold distance

- k-nearest neighbors - k closest centroids

Adjacency Matrix Neighborhood structure encoded in matrix $\mathbf{W}$: $$w_{ij} = \begin{cases} 1 & \text{if } i \text{ and } j \text{ are neighbors} \ 0 & \text{otherwise} \end{cases}$$

Areal Data: Method 1 - CAR Models

Conditional Autoregressive (CAR) Models

Each area’s random effect depends on its neighbors:

$$w_i | \mathbf{w}{-i}, \tau^2 \sim \text{Normal}\left(\sum{j \sim i} b_{ij}w_j, \tau_i^2\right)$$

Most common: Intrinsic CAR (ICAR)

$$w_i | \mathbf{w}{-i}, \tau^2 \sim \text{Normal}\left(\frac{1}{n_i}\sum{j \sim i} w_j, \frac{\tau^2}{n_i}\right)$$

Where $n_i$ = number of neighbors of area $i$.

ICAR Model: Properties

Interpretation: Each area’s value is the average of its neighbors, plus noise.

Key properties:

- Induces strong spatial smoothing

- Prior is improper (infinite variance)

- Requires sum-to-zero constraint: $\sum_i w_i = 0$

- Variance proportional to $1/n_i$ (islands have high variance!)

Island Problem Areas with few neighbors have high uncertainty. Consider removing islands or using proper CAR.

Areal Data: Method 2 - Proper CAR

Adds spatial decay parameter $\rho$ to control smoothing strength:

$$w_i | \mathbf{w}{-i}, \tau^2, \rho \sim \text{Normal}\left(\frac{\rho}{n_i}\sum{j \sim i} w_j, \frac{\tau^2}{n_i}\right)$$

Properties:

- $\rho = 0$ → independent random effects (no spatial structure)

- $\rho \to 1$ → approaches ICAR (maximum smoothing)

- Proper prior (finite variance)

- Can estimate $\rho$ from data

When to use: When you want data to determine smoothing strength.

Areal Data: Method 3 - BYM Model

Besag-York-Mollié (BYM) Model - convolution of spatial and non-spatial effects:

$$w_i = u_i + v_i$$

Where:

- $u_i \sim \text{ICAR}(\tau_u^2)$ → spatially structured

- $v_i \sim \text{Normal}(0, \tau_v^2)$ → unstructured

Advantage: Separates spatial and non-spatial variation

BYM2 Parameterization

Modern version uses a mixing parameter $\phi \in [0,1]$: $$w_i = \frac{1}{\sqrt{\tau}}(\sqrt{\phi} \cdot u_i + \sqrt{1-\phi} \cdot v_i)$$ Easier to specify priors!

Areal Data: Method 4 - SAR Models

Simultaneous Autoregressive (SAR) Models

Different from CAR! Response depends on neighbors’ responses:

$$\mathbf{y} = \rho \mathbf{W}\mathbf{y} + \mathbf{X}\boldsymbol{\beta} + \boldsymbol{\epsilon}$$

Key difference:

- CAR: Spatial dependence in random effects

- SAR: Spatial dependence in response variable itself

- SAR has “spillover” effects (feedback loops)

Implementation: spdep package in R

Areal Data: CAR vs SAR

| Feature | CAR | SAR |

|---|---|---|

| What’s spatial? | Random effects | Response variable |

| Interpretation | Smoothing | Spillover/feedback |

| Computation | Easy (INLA) | More complex |

| Bayesian | Yes | Possible but harder |

| Ecology use | Very common | Less common |

In Practice CAR models are much more common in ecology. SAR models used more in econometrics.

Areal Data: Method 5 - Spatial Eigenvectors

Moran’s Eigenvector Maps (MEM) / PCNM

Idea: Decompose spatial relationships into orthogonal eigenvectors

- Create distance/connectivity matrix

- Eigendecompose to get spatial filters

- Use eigenvectors as covariates in regression

$$y_i = \beta_0 + \sum_{k=1}^K \beta_k \text{EV}_{ik} + \epsilon_i$$

Advantages:

- Works with any spatial configuration

- Frequentist framework (familiar to many ecologists)

- Can select eigenvectors (forward selection)

Spatial Eigenvectors: Example

library(adespatial)

library(spdep)

# Create neighborhood structure

coords <- st_coordinates(st_centroid(polygons))

nb <- poly2nb(polygons)

# Generate spatial eigenvectors

mem <- scores.listw(nb2listw(nb),

wt = coords,

MEM.autocor = "positive")

# Use in regression

model <- lm(abundance ~ covariate1 + covariate2 +

MEM1 + MEM2 + MEM3, data = mydata)

# Or select eigenvectors via forward selection

mem.sel <- forward.sel(y = mydata$abundance,

x = mem$vectors,

alpha = 0.05)

Areal Data: Comparison

| Method | Framework | Smoothing | Flexibility | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICAR | Bayesian | Strong | Low | Small n, strong spatial signal |

| Proper CAR | Bayesian | Data-driven | Medium | Estimate smoothing strength |

| BYM/BYM2 | Bayesian | Flexible | High | Separate spatial/non-spatial |

| SAR | Frequentist | Feedback | Medium | Spillover processes |

| MEM | Frequentist | Data-driven | High | Flexible, frequentist |

Areal Data: R Example with INLA

library(INLA)

library(spdep)

library(sf)

# Load spatial data

regions <- st_read("regions.shp")

# Create neighborhood structure

nb <- poly2nb(regions)

nb2INLA("region.adj", nb) # Save adjacency for INLA

# Prepare data

data <- st_drop_geometry(regions)

data$region_id <- 1:nrow(data)

# BYM2 model

formula <- cases ~

covariate1 +

covariate2 +

f(region_id,

model = "bym2",

graph = "region.adj",

hyper = list(

prec = list(prior = "pc.prec", param = c(1, 0.01)),

phi = list(prior = "pc", param = c(0.5, 0.5))

))

result <- inla(

formula,

family = "poisson",

data = data,

E = data$expected, # For disease mapping

control.predictor = list(compute = TRUE),

control.compute = list(dic = TRUE, waic = TRUE)

)

# Extract spatial random effects

spatial_effects <- result$summary.random$region_id

# Map results

regions$fitted <- result$summary.fitted.values$mean

plot(regions["fitted"])

3. Point Pattern Data

When locations themselves are the response

What is Point Pattern Data?

Definition: The spatial locations of events/individuals are what we’re modeling.

Ecological Examples:

- Tree locations in a forest plot

- Animal sightings/occurrences

- Nest locations of colonial birds

- Burrow entrances

- Lightning strike locations

Key characteristic: The pattern of locations is the phenomenon of interest, not a measurement at those locations.

Point Pattern: Visual Example

Key questions:

- Random, clustered, or regular?

- Does intensity vary across space?

- What drives the spatial pattern?

- Interaction between points?

Three Main Patterns

- Random (CSR - Complete Spatial Randomness)

- Clustered (aggregated, contagious)

- Regular (dispersed, uniform, inhibition)

Point Pattern: Core Concept - Intensity

Intensity function $\lambda(\mathbf{s})$ = expected number of points per unit area at location $\mathbf{s}$

$$\mathbb{E}[N(A)] = \int_A \lambda(\mathbf{s}) d\mathbf{s}$$

Types:

- Homogeneous: $\lambda(\mathbf{s}) = \lambda$ (constant)

- Inhomogeneous: $\lambda(\mathbf{s})$ varies with location

- Can depend on covariates: $\lambda(\mathbf{s}) = \exp(\mathbf{X}(\mathbf{s})\boldsymbol{\beta})$

Point Pattern: Method 1 - Inhomogeneous Poisson Process

Simplest model: Points are independent given intensity function

$$\lambda(\mathbf{s}) = \exp(\beta_0 + \beta_1 x_1(\mathbf{s}) + … + \beta_p x_p(\mathbf{s}))$$

Fitting:

- Divide study area into grid/quadrats

- Count points per cell

- Fit Poisson GLM or use

spatstatfor continuous intensity

Assumption Points are independent - no interaction or clustering beyond what covariates explain.

Point Pattern: Method 2 - Cox Processes

Adds spatial random effects to intensity:

$$\lambda(\mathbf{s}) = \exp(\mathbf{X}(\mathbf{s})\boldsymbol{\beta} + w(\mathbf{s}))$$

Where $w(\mathbf{s})$ is a spatial Gaussian process.

Types:

- Log-Gaussian Cox Process (LGCP) - GP on log-intensity

- Shot-noise Cox Process - clusters around random parent points

Result: Accounts for residual spatial clustering not explained by covariates.

LGCP: Implementation Approaches

Approach 1: Discretize space

- Divide area into fine grid

- Model counts per cell with spatial random effects

- Use INLA with SPDE

Approach 2: Integrated nested Laplace approximation

- Direct likelihood for point pattern

- Continuous intensity surface

- Package:

inlabruin R

Point Pattern: Method 3 - Interaction Models

For processes with point-to-point interaction:

$$\lambda(\mathbf{s} | \text{other points}) = \lambda(\mathbf{s}) \times g(\text{distances to other points})$$

Types:

- Hard-core: Minimum distance between points

- Strauss process: Inhibition within distance $r$

- Geyer saturation: Limited inhibition strength

Use when: Points repel or attract each other (territoriality, facilitation).

Package: spatstat in R for interaction models

Point Pattern: Comparison

| Model Type | Complexity | Interaction | Spatial Trend | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poisson | Low | None | Yes (via covariates) | Independent points |

| LGCP | Medium | Apparent (via GP) | Yes | Clustering from environment |

| Hard-core | Medium | Strong repulsion | Yes | Territorial species |

| Strauss | High | Tunable | Yes | Flexible interaction |

Point Pattern: R Example with spatstat

library(spatstat)

# Create point pattern object

pp <- ppp(x = trees$x, y = trees$y,

window = owin(c(0, 100), c(0, 100)))

# Test for complete spatial randomness

plot(envelope(pp, Kest)) # K-function envelope test

# Fit inhomogeneous Poisson with covariates

# Create spatial covariates

elevation_im <- as.im(elevation_raster)

# Fit model

fit_pois <- ppm(pp ~ elevation + I(elevation^2),

covariates = list(elevation = elevation_im))

# Fit log-Gaussian Cox process

fit_lgcp <- kppm(pp ~ elevation,

clusters = "LGCP",

covariates = list(elevation = elevation_im))

# Compare models

AIC(fit_pois)

AIC(fit_lgcp)

# Predict intensity

pred_intensity <- predict(fit_lgcp)

plot(pred_intensity)

Point Pattern: R Example with inlabru

library(inlabru)

library(INLA)

library(sp)

# Prepare data

points <- SpatialPoints(cbind(trees$x, trees$y))

boundary <- SpatialPolygons(list(Polygons(list(Polygon(

matrix(c(0,0, 100,0, 100,100, 0,100, 0,0), ncol=2, byrow=TRUE)

)), "boundary")))

# Create mesh

mesh <- inla.mesh.2d(

boundary = boundary,

max.edge = c(5, 10),

cutoff = 2

)

# Define LGCP model with covariates

cmp <- coordinates ~

Intercept(1) +

elevation(elevation_data, model = "linear") +

spatial(coordinates,

model = inla.spde2.matern(mesh))

# Fit model

fit <- lgcp(

cmp,

data = points,

domain = list(coordinates = mesh),

options = list(control.inla = list(int.strategy = "eb"))

)

# Predict intensity surface

pred_coords <- expand.grid(

x = seq(0, 100, length = 100),

y = seq(0, 100, length = 100)

)

predictions <- predict(

fit,

pred_coords,

~ exp(Intercept + elevation + spatial)

)

3. Movement / Trajectory Data

GPS tracks, telemetry, and animal paths

What is Movement Data?

Definition: Locations of individuals tracked through time, creating paths or trajectories.

Ecological Examples:

- GPS collars on mammals

- Bird migration tracks

- Fish acoustic telemetry

- Insect flight paths

- Marine turtle tracking

Key characteristic: Data have temporal and spatial structure; autocorrelation in both dimensions.

Movement Data: Visual Example

Typical data structure:

- Individual ID

- Timestamp

- Longitude, Latitude

- Environmental covariates

- Behavioral state (sometimes)

Key Questions

- What drives movement decisions?

- How do animals select habitat?

- Can we identify behavioral states?

- What’s the home range?

- How do individuals differ?

Movement Data: Unique Challenges

Multiple sources of autocorrelation:

- Temporal: Location at $t$ depends on $t-1$

- Spatial: Nearby environmental conditions are similar

- Individual: Each animal has consistent behavior

Observation models:

- GPS error (location uncertainty)

- Irregular sampling intervals

- Missing data

Standard spatial models don’t account for movement process!

Movement Data: Method 1 - Step Selection Functions

Idea: Model animal’s choice among available steps at each time point

$$w(\mathbf{s}t | \mathbf{s}{t-1}) \propto \exp(\beta_1 x_1(\mathbf{s}_t) + … + \beta_p x_p(\mathbf{s}_t))$$

Steps:

- For each observed step, generate “available” alternative steps

- Compare chosen vs available using conditional logistic regression

- Covariates describe step characteristics (length, angle, habitat)

Interpretation: Habitat selection during movement

Step Selection Functions: Details

Used step: What the animal actually did $$\text{step length}, \quad \text{turn angle}, \quad \text{end habitat}$$

Available steps: What it could have done

- Sample from movement kernel (e.g., gamma distribution for length)

- Usually 10-100 available steps per used step

Model:

$$\text{Pr(step chosen)} = \frac{\exp(\mathbf{X}\boldsymbol{\beta})}{\sum_{j=1}^n \exp(\mathbf{X}_j\boldsymbol{\beta})}$$

SSF: R Example

library(amt)

library(survival)

# Prepare tracking data

track <- make_track(gps_data,

.x = x, .y = y, .t = timestamp,

id = animal_id, crs = 32612)

# Create steps

steps <- track %>%

steps_by_burst()

# Generate random available steps (20 per used)

rand_steps <- steps %>%

random_steps(n_control = 20)

# Extract habitat at end of each step

rand_steps <- rand_steps %>%

extract_covariates(habitat_raster) %>%

extract_covariates(elevation_raster)

# Fit conditional logistic regression (step selection function)

ssf_model <- rand_steps %>%

fit_clogit(case_ ~

forest +

elevation +

I(elevation^2) +

sl_ + log_sl_ + # Step length terms

cos_ta_ + # Turn angle

strata(step_id_))

summary(ssf_model)

Movement Data: Method 2 - State-Space Models

Two-level model:

-

Movement process (latent true locations): $$\mathbf{s}t = \mathbf{s}{t-1} + \mathbf{v}_t$$

-

Observation process (GPS measurements): $$\mathbf{y}_t = \mathbf{s}_t + \boldsymbol{\epsilon}_t$$

Advantages:

- Accounts for GPS error

- Handles irregular sampling

- Can incorporate behavior

- Smooths erratic paths

State-Space Models: Behavioral States

Hidden Markov Models (HMM): Switch between behavioral states

Example states:

- Encamped (resting, feeding)

- Exploratory (traveling, migrating)

Each state has different movement parameters:

- State 1: Short steps, high turning

- State 2: Long steps, low turning

$$\begin{bmatrix} p_{11} & p_{12} \ p_{21} & p_{22} \end{bmatrix} \leftarrow \text{Transition matrix}$$

State-Space Model: R Example

library(momentuHMM)

# Prepare data

data <- prepData(gps_data,

type = "UTM",

coordNames = c("x", "y"))

# Define 2-state model parameters

# State 1: encamped, State 2: traveling

# Step length distributions (Gamma)

stepPar0 <- c(

mean_state1 = 100, # Short steps when encamped

mean_state2 = 1000, # Long steps when traveling

sd_state1 = 50,

sd_state2 = 500

)

# Turning angle distributions (von Mises)

anglePar0 <- c(

mean_state1 = 0, # Random turning

mean_state2 = 0, # Directional

concentration_state1 = 0.1, # Low concentration

concentration_state2 = 0.8 # High concentration

)

# Fit HMM

hmm_fit <- fitHMM(

data = data,

nbStates = 2,

dist = list(step = "gamma", angle = "vm"),

Par0 = list(step = stepPar0, angle = anglePar0)

)

# Decode states (Viterbi algorithm)

states <- viterbi(hmm_fit)

# Plot results

plot(hmm_fit)

plotStates(hmm_fit)

Movement Data: Method 3 - Continuous-Time Models

Problem: Discrete-time models assume regular intervals

Solution: Continuous-time movement models handle irregular sampling

Common approach: Ornstein-Uhlenbeck process

$$d\mathbf{s}_t = -\mathbf{B}(\mathbf{s}_t - \boldsymbol{\mu})dt + \boldsymbol{\Sigma}^{1/2}d\mathbf{W}_t$$

Interpretation:

- $\boldsymbol{\mu}$ = “home range center”

- $\mathbf{B}$ = rate of return to center

- $\boldsymbol{\Sigma}$ = movement variability

Continuous-Time: ctmm Package

library(ctmm)

# Prepare telemetry object

telemetry_obj <- as.telemetry(gps_data)

# Fit variogram (explore temporal autocorrelation)

vario <- variogram(telemetry_obj)

plot(vario)

# Guess movement model parameters

guess <- ctmm.guess(telemetry_obj,

interactive = FALSE)

# Fit Ornstein-Uhlenbeck model

fit_ou <- ctmm.fit(telemetry_obj, guess)

# Calculate home range

home_range <- akde(telemetry_obj, fit_ou)

plot(home_range)

# Summary

summary(fit_ou)

summary(home_range)

Movement Data: Method 4 - Integrated Models

Combine step selection with state-space models

Advantages:

- SSF for habitat selection

- State-space for behavioral states and GPS error

- Best of both worlds!

Implementation:

bsampackage (Bayesian state-space models)- Custom JAGS/Stan models

crawlpackage for state-space + habitat

Movement Data: Comparison

| Method | Temporal Structure | Habitat Selection | Behavioral States | GPS Error |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SSF | Discrete steps | Yes | No | No |

| HMM | Discrete time | Possible | Yes | No |

| State-Space | Continuous | Limited | Yes | Yes |

| Integrated | Both | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Start Simple Begin with SSF for habitat selection, add state-space if GPS error or behavioral switching is important.

Integrating Across Data Types

Real ecological studies often involve multiple spatial data types

Multi-Scale / Multi-Type Integration

Common scenarios:

- Point + Areal: Bird surveys (points) + land cover (areal)

- Point + Movement: Home range (movement) + resource selection (points)

- Point Pattern + Covariates: Tree locations + soil maps

- Movement + Remote Sensing: Tracks + NDVI time series

The Challenge Different data types have different spatial support, resolution, and uncertainty.

Integration Approach 1: Change of Support

Problem: Data at different spatial scales

Example:

- Response: Point-level species occurrence

- Covariates: Areal land cover by county

Solutions:

- Aggregate points to areal units (lose resolution)

- Downscale areal to points (assumes homogeneity)

- Model explicitly with geostatistical fusion (best but complex)

Integration Approach 2: Joint Likelihood Models

Idea: Model all data types simultaneously with shared parameters

Example: Integrated Species Distribution Model (ISDM)

- Data source 1: Structured surveys (presence-absence)

- Data source 2: Opportunistic sightings (presence-only)

- Data source 3: Telemetry tracks (habitat use)

Shared parameter: True intensity/abundance surface $\lambda(\mathbf{s})$

Implementation: PointedSDMs package in R

Integration Approach 3: Spatial Misalignment

When spatial supports don’t match:

$$\begin{aligned} \text{Point data:} \quad & Y_p(\mathbf{s}) = f(\lambda(\mathbf{s})) \ \text{Areal data:} \quad & Y_A(R) = g\left(\int_R \lambda(\mathbf{s})d\mathbf{s}\right) \end{aligned}$$

Model latent process $\lambda(\mathbf{s})$ and link to both:

- Point process observation model

- Aggregation to areal support

Package: areal in R for interpolation

Practical Integration Example

Scenario: Modeling lynx habitat selection

Data sources:

- GPS telemetry (movement data)

- Camera trap detections (point pattern)

- Forest cover by grid cell (areal)

- Prey abundance point surveys (point-referenced)

Approach:

- Use SSF for fine-scale habitat selection from GPS

- Use LGCP for broad-scale intensity from cameras

- Extract covariates from areal forest data

- Create prey abundance surface from surveys (kriging/SPDE)

- Link all through shared spatial random effect

Model Selection and Validation

How do we choose and evaluate spatial models?

Validation for Spatial Data

Critical Issue

Standard cross-validation is wrong for spatial data!

Nearby points are autocorrelated, so “test” data are not independent of “training” data.

Solution: Spatial cross-validation

- Spatial blocking: Leave out spatial blocks

- Leave-location-out: Remove all data near test points

- Clustered CV: Remove spatial clusters

Spatial Cross-Validation Methods

1. Spatial blocking:

library(blockCV)

# Create spatial blocks

blocks <- cv_spatial(

x = species_data,

column = "presence",

k = 5, # 5-fold CV

size = 50000, # 50km blocks

selection = "random"

)

# Use blocks for CV

cv_results <- cv_spatial_fold(

model, blocks

)

2. Leave-region-out:

- Hold out entire regions (e.g., one study site)

- Tests spatial transferability

Model Comparison for Spatial Models

Information criteria:

- WAIC (Widely Applicable IC) - for Bayesian models

- DIC - Bayesian, but can be problematic for spatial models

- Spatial AIC - adjusts for effective sample size

Predictive performance:

- Mean squared prediction error (MSPE)

- Continuous ranked probability score (CRPS)

- Log-likelihood on held-out data

Best Practice Use spatial CV + predictive metrics, not just information criteria.

Diagnosing Spatial Model Fit

Check residual autocorrelation:

- Moran’s I test

library(spdep)

moran.test(residuals(model), nb2listw(neighbors))

- Variogram of residuals

library(gstat)

v <- variogram(residuals ~ 1, locations = ~x+y, data = data)

plot(v) # Should be flat if spatial structure captured

- Spatial correlograms

Residuals should show no spatial autocorrelation if model is adequate!

Computational Considerations

| Data Type | Typical n | Fast Methods | Slow but Flexible |

|---|---|---|---|

| Point-referenced | 100-10,000 | Splines (mgcv), SPDE | Full GP |

| Areal | 50-5,000 | CAR (INLA), MEM | Complex interaction models |

| Point pattern | 100-100,000 | Discretized LGCP | True LGCP |

| Movement | 1,000-100,000 | SSF, HMM | State-space, continuous-time |

Modern Trend Approximate methods (INLA, SPDE, low-rank GPs) make complex spatial models feasible for large ecological datasets.

Software Summary

R Packages by data type:

Point-referenced: mgcv, INLA, inlabru, gstat, spBayes

Areal: INLA, CARBayes, spdep, adespatial

Point pattern: spatstat, inlabru, ppmlasso

Movement: amt, momentuHMM, ctmm, crawl, adehabitatLT

Multi-purpose: sf, terra, sp (spatial data structures)

Recommended Workflow

- Visualize data - maps, variograms, spatial correlograms

- Start simple - non-spatial model, then add space

- Choose method based on data type and question

- Fit multiple models - compare approaches

- Validate spatially - spatial CV or block CV

- Diagnose residuals - check for remaining spatial structure

- Interpret carefully - spatial effects ≠ causal mechanisms

Don’t Overfit! More complex ≠ better. Use simplest model that captures spatial structure.

Common Pitfalls

Watch Out For:

- Confounding: Spatial effects absorbing true covariate effects

- Edge effects: Boundary areas have high uncertainty

- Non-stationarity: Spatial structure varies across landscape

- Anisotropy: Spatial correlation depends on direction

- Computational limits: Be realistic about data size

- Over-smoothing: Too much spatial structure removes real variation

- Ignoring uncertainty: Report it! Especially for predictions

When to Use Each Data Type Approach

Use point-referenced methods when:

- You have lat/lon coordinates from surveys

- Want to predict continuous surface

- Sample size: 50-10,000 locations

Use areal methods when:

- Data aggregated to regions/cells

- Clear neighborhood structure

- Often: count data, rare events

Use point pattern methods when:

- Locations are the outcome of interest

- Want to model spatial intensity

- Concern: point-to-point interactions

Use movement methods when:

- Tracking individuals over time

- Interested in habitat selection during movement

- Need to account for temporal autocorrelation

Future Directions

Emerging methods:

- Deep learning for spatial prediction

- Spatial conformal inference (uncertainty quantification)

- Multi-resolution models

- Non-stationary spatial processes

- Real-time spatial models (citizen science, camera traps)

- Massive-scale spatial models (>1 million locations)

Software development:

- Better integration across data types

- User-friendly interfaces for complex models

- Improved computational efficiency

Key Takeaways

Remember:

- Data structure determines appropriate methods - identify your data type first

- Start simple, add complexity as needed - parsimony matters

- Validate spatially - standard CV fails with spatial data

- Computational feasibility - consider dataset size and resources

- Interpretation - spatial structure helps prediction but may obscure causation

- Residual diagnostics - always check for remaining spatial autocorrelation

Resources

Books:

- Banerjee et al. (2014) Hierarchical Modeling and Analysis for Spatial Data

- Cressie & Wikle (2011) Statistics for Spatio-Temporal Data

- Illian et al. (2008) Statistical Analysis and Modelling of Spatial Point Patterns

Papers:

- Lindgren et al. (2011) “An explicit link between Gaussian fields and Gaussian Markov random fields” JRSS-B

- Hooten et al. (2017) “Animal Movement Models for Spatial Ecology” Wiley

Online:

Questions?

Contact & Discussion

- Email: jbaecher@gmail.com

- Website: www.alexbaecher.com

- GitHub: @slamander

What spatial data challenges are you facing?

Let’s discuss specific applications to your research!

Thank you!